Following online conduct, Boricuas Unidos en la Diaspora is banned from Twitter

The Puerto Rico advocacy political group Boricuas Unidos en la Diáspora (BUDPR) was recently banned from Twitter on account of hateful conduct. The organization defines itself as an “international network of Puerto Ricans who seek to generate direct, long-lasting, community-led social change in Puerto Rico”, focusing on topics ranging from self-determination and decolonization to public debt and sustainability. Their emphasis on uniting the Puerto Rican diaspora to better the wellbeing and provide change to the region has persisted since 2017 when they initially formed to combat the effects of Hurricane Maria. Since the pandemic, BUDPR has been more and more active online, where they have spread their education and advocacy—but more recently where they have been accused of spreading misinformation and targeting users.

El mundo es un mejor lugar, luego de la suspensión de la cuenta de @BUnidosDPR, de @edilantoniopr. Sólo lamento no haber sido yo quien lo lograra. pic.twitter.com/7GrQU7J9mP

— The Captain 🇺🇲🇵🇷 (@PicardTheCapt) February 9, 2022

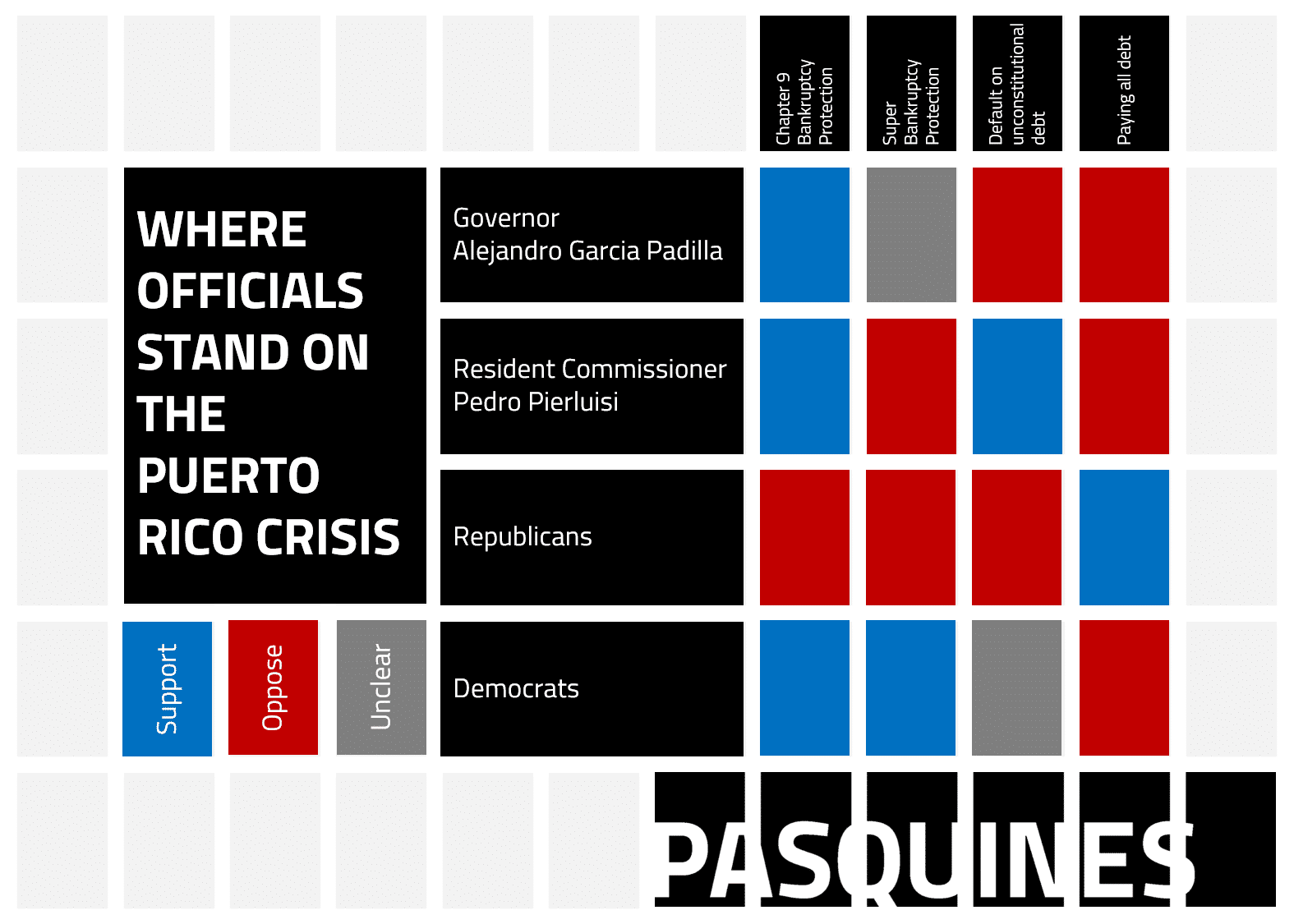

Within the past two years, many characterize BUDPR’s online presence as saying “outlandish things about anybody who was perceived as supporting statehood,” according to Eliot Tricotti, director of political data visualization project Boricuas4Democracy. BUDPR has been very vocal about its opposition towards Puerto Rican statehood—attacking people that express pro-statehood opinions online and to “…amplify whatever vitriol is heading towards any of their enemies, real or perceived”, according to Tripoli. Many share sentiments with Tripoli, feeling as if BUDPR’s personal attacks to anyone who supported statehood cross a line- some calling BUDPR out for xenophobia or homophobia. Despite this, Edil Sepulveda, co-founder of BUDPR, argues that the “hateful conduct” that got the organization’s account banned was not their attacks but rather their advocacy for #GringoGoHome movement. He attributes the ban of their account to a tweet of a poster for the “March for Decolonization, Not Statehood” stating “Los Yankis Quieren Fuego” with a depiction of a molotov cocktail. “I defend everything that we have said…we have the total legitimacy to say that” Sepulveda argues. “In a colonial relationship, the oppressed can say anything they want.”

Image tweeted by Boricuas Unidos en la Diaspora, seemingly inciting violence against Americans.

Many have also called out BUDPR for amplifying hate towards Ritchie Torres, the representative for New York’s 15th Congressional District, who is also the first openly gay Afro-Latino elected to Congress. Torres is a strong advocate for Puerto Rican statehood and wrote an op-ed on the importance of statehood. When a tweet from a suspended account responded to Torres by calling him an “Uncle Tom ”, BUDPR liked the comment. Where many point to xenophobia at the root of this online interaction, Sepulveda emphasizes that “We only attack people for being pro-statehood” and the accusations of xenophobia and homophobia were “[n]ever in writing.” Some assert that BUDPR has endorsed anti-semitic sentiments from other accounts as well as spread misinformation regarding Puerto Rican statehood, putting an “incredible amount of spin it amounts to disinformation” according to Tripoli to numerous stories to further their anti-statehood agenda.

BUDPR’s anti-statehood sentiment extended far beyond social media. On December 8, 2021, BUDPR sent a letter to Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer lobbying against the Build Back Better program which has provided Social Security programs and Medicaid. In the letter, they assert that the pro-statehood party is supporting the Build Back Better Program to “…perpetuate territorial dependency on federal funds and bring Puerto Rico closer to statehood…” Many on Twitter have noted the importance of Build Back Better for many Puerto Ricans.

El grupo BUDPR cabildea EN CONTRA de la extensión de beneficios de Seguridad de Ingreso Suplementario (SSI) y EN CONTRA del aumento en fondos Medicaid.

En una carta al Senador Schumer, dicen que la paridad en programas federales es un plan “pro-estadidad”, ignorando… pic.twitter.com/8wKscsP37X

— Eliot S. Tricotti Mookarjee🇵🇷 (@eliottricotti) December 8, 2021

Both pro-statehood and pro-independence individuals in Puerto Rico have opposing viewpoints on why BUDPR was banned. When asked about the reason behind pro-statehood attacks, both Sepulveda and Tripoli point to nationalism, but of different kinds. The attacks on statehood supporters “come from us being nationalists’ ‘ Sepulveda highlights. “For us, nationalism is a way of surviving, to not assimilate to the empire”, Sepulveda notes. Nationalism is an undercurrent of BUDPR’s agenda.

In contrast, Tricotti highlights that “there is an undercurrent in Puerto Rico…of ethnic nationalism” and that the nationalism that BUDPR is catalyzed by is one that dislikes the Puerto Rican race “…being dirty with non- Puerto Rican blood” and “questioning if people” are Puerto Rican “enough.” He says they have “racialized” the discourse on nationalism. Tricotti clarifies that although he is not a pro-statehood activist, he has received attacks from BUDPR- something he attributes to ethnic nationalism and the belief that he is not Puerto Rican “enough.”

After being banned, BUDPR has made a new account. “We know where we stand,” Sepulveda asserts. “We are not going to prevent them from censoring us” and that they will be “[s]trategic without renouncing our way of being.” He strongly believes that because of the colonial power dynamics in Puerto Rico, the oppressed should be able to say what they want. “I stand by everything we have said.”