This is the first in a series of articles examining the United States and its relationship with the territories, marking a decade after Pasquines’ founding.

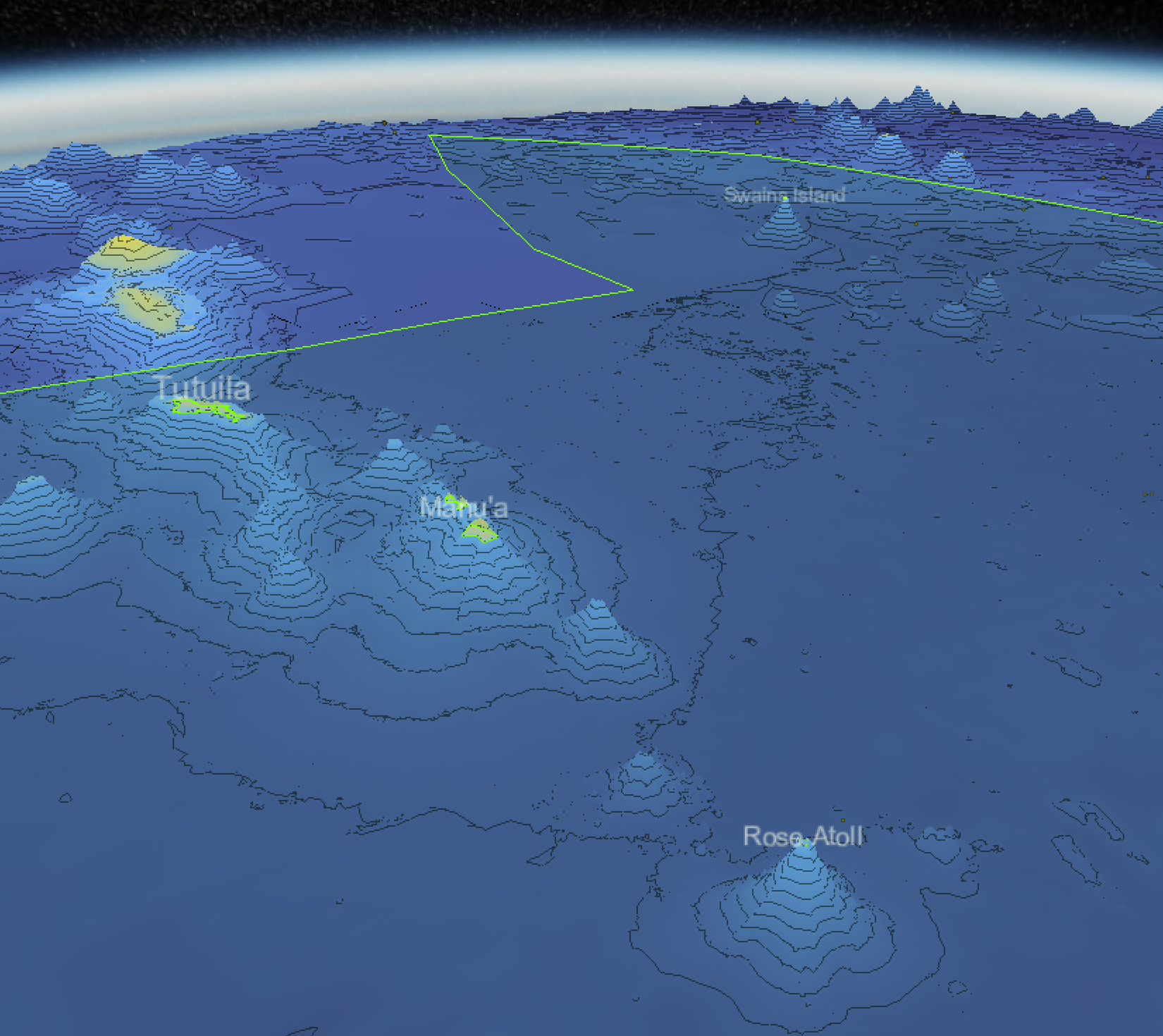

Cays, islands, archipelagos. Up until the late fifteenth century, the existence of the places we know now as Puerto Rico, Guam, the United States Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands was largely unknown to Western civilization. Upon first contact with the indigenous inhabitants of these places, new names come into the picture: Boriken, Guåhan, Manuá tele. The role of and context of perception would be undeniable.

As destiny would have it, these indigenous denominations would give way to new ones. Isla de los Ladrones, Santa Úrsula y las Once Mil Vírgenes, San Juan Bautista. In some cases, the people residing in these places would also get new denominations. Spanish, Danish, German, Japanese, and American colonial powers would fundamentally transform the identity of these islands and, thereby, the perception of them and their residents forever after.

In many ways, the perceptions the Europeans had in the middle of the last millennium of these islands we’ve covered for the last ten years still permeate to this day.

Insular, overseas, unincorporated

These are islands and archipelagos in the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean that are under the jurisdiction of the US but do not have full political representation or equal rights as the 50 states and or even the District of Columbia. The residents of these territories are US citizens (except for American Samoa, where they are non-citizen nationals, a status akin to that of a US resident), but they cannot vote for president, have no voting members in Congress, and are subject to different tax laws and federal programs than the rest of the country.

Geographically separated by thousands of miles from the mainland US, life in the territories has developed under, at times, severely heinous perceptions from outsiders that, to this day, still shape fundamental aspects of what means to live in an unincorporated territory. “Alien races” and “savage tribes” is what the Supreme Court of the United States called the residents of the US’ possessions at the turn of the twentieth century, using their racist ideology to create the very concept of an unincorporated territory. Their impact still lingers in the legal and political status of the territories today.

Foreign, in a domestic sense

The Supreme Court’s invention of a new colonial structure evidently shaped the American context of perception of the territories. Even in our modern times of social media and misinformation, the court’s influence is clear.

According to a 2017 survey by Morning Consult, most Americans are unaware of basic facts about the US territories. Only 54% of respondents knew Puerto Ricans are US citizens. Google Trends also validates this perception. Look at the last decade comparing search interest for Puerto Rico versus Utah and Iowa—the two closest states in terms of population size—and the difference is stark.

This might help explain why Morning Consult didn’t even ask about the other four territories in their poll. They might not have had to: a look at Google Trends shows an abysmal difference in search interest between Puerto Rico and the other territories.

If Puerto Ricans, arguably the most popular among territorial residents, are barely considered American, you can guess what the results would look like for the other four.

With racist and colonialist perspectives shaping the legal framework of the territories in the United States, one can almost start seeing a domino effect that has now become a self-reinforcing mechanism. The Insular Cases helped shaped the perspectives of the people in the territories, and these perspectives now show in datasets of the twenty-first century. Ask Microsoft’s ChatGPT-powered Bing about American perspectives of the territories and the lack of knowledge about them, and it provides answers like these:

“Another possible explanation is the geographical and cultural distance that separates most Americans from the territories. The territories are located thousands of miles away from the mainland US, and have distinct histories, languages, cultures, and identities that are often overlooked or misunderstood by mainlanders.“

Never mind the differences in histories, languages, cultures, and identities between the states themselves, let alone the more than 574 tribal nations in the United States. The idea of the territories being distinct and separate is now pervasive, and the consequences are very real.

Commonwealth, colony, context of perception

As the charts above show, there have been moments where attention spikes for Puerto Rico and Guam—every time something bad happens. Hurricane Maria got Puerto Rico the most attention in the last decade, and former president Donald Trump’s relationship with North Korea caused Guam to show up on the radar of national media outlets. But even then, we have beyond enough evidence that that coverage pales in comparison to what states get, whether they’re called commonwealths, territories, or colonies.

“In this case, the lack of media attention could lead people to ignore Puerto Rico’s plight. Our sympathies for other people depends in part on whether we see them as fellow members of our tribe. Without more coverage, it may be easy to forget that the people suffering are our fellow Americans.”

Kyle Dropp

Knowing that, the effects then become clear. Kyle Dropp summarized it best in 2017 when he stated that “In this case, the lack of media attention could lead people to ignore Puerto Rico’s plight. Our sympathies for other people depends in part on whether we see them as fellow members of our tribe. Without more coverage, it may be easy to forget that the people suffering are our fellow Americans.”

There is no better example of this playing out in real life than with Puerto Rico. Blocked, less-generous-than-in-the-states aid, which in some cases has yet to even make it, still affects life for the worse in the territory.

The unequal treatment created by warped, racist contexts of perception have developed into an unsustainable framework, which then further accentuates that idea of separation. Even when glimmers of change appear, they are few and far between and still don’t get to address inequities between the other territories other than Puerto Rico. Bing did get to realize part of the problem, stating that the challenges the territories face “are often ignored or distorted by mainstream media and popular culture, which tend to portray the territories as exotic paradises for tourism or as impoverished disaster zones for pity. These stereotypes not only dehumanize and marginalize the people of the territories but also obscure their contributions and potential to the nation.” Say less.

This publication has been covering the context of islands for a decade. In that span of time—of hurricanes, typhoons, earthquakes (physical and political), a pandemic, civil rights movements, and economic uncertainty—one thing has remained the same: the unequal treatment of the United States’ unincorporated territories. The perceptions that helped create this situation—legal, political, informational, and economic—still pervade, as strong as ever.

This is an interesting item: https://docs.house.gov/meetings/II/II00/20210512/112617/HHRG-117-II00-20210512-SD1100.pdf