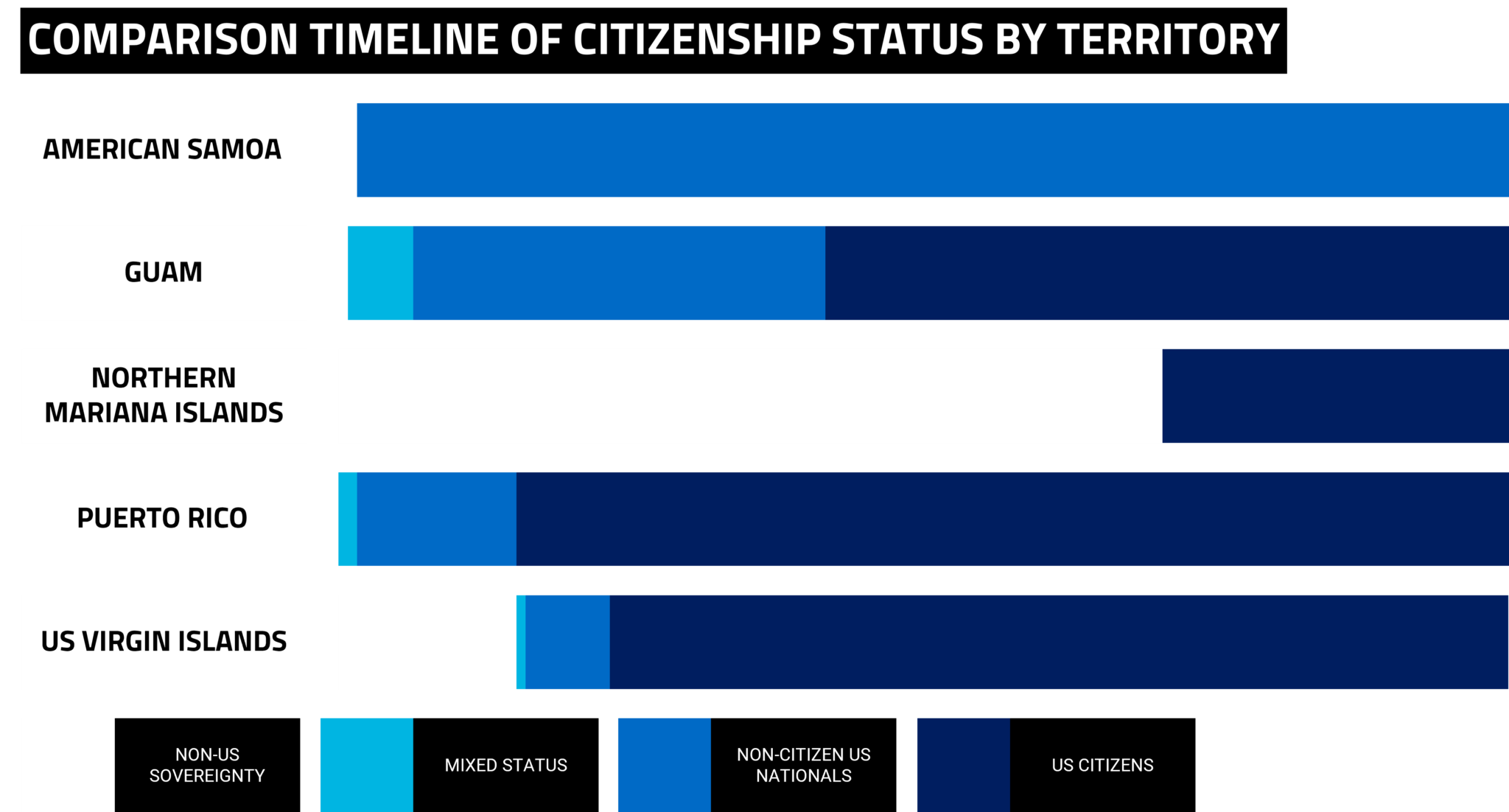

The concept and context of citizenship in the United States unincorporated territories has always been a complex one, fraught with legal battles, unequal application of rights, and controversies that remain to this day. Under the present scheme, where residents of Puerto Rico, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, and the Northern Mariana Islands have been granted birthright US citizenship, issues still arise when it comes to the application of the US Constitution, federal laws, and local governance. Those issues and intricacies become even more pronounced in American Samoa, where locals are considered noncitizen US nationals, a status akin to that of a US permanent resident.

Subject to a hodgepodge of federal nationality and citizenship laws, court decisions, and executive regulations, the history and application of citizenship in each territory have a unique, convoluted history. The consequences of this history are felt differently in each territory; while Northern Marian Islands residents pay federal taxes, those in Puerto Rico don’t; while the US Virgin Islands immigration system is controlled by federal authorities, in American Samoa, it’s the local government who is in charge.

Political, immigration, economic, cultural, and governance factors all play a role in the discussion of citizenship in the territories. And although, at present, most of them are governed under the same structure of automatic US citizenship at birth, the realities in the islands, and the path forward, are all very different.

Colonial subjects

Prior to the United States, the governments of Spain, Denmark, Germany, and Japan all had colonial control over one or more of the territories and therefore controlled citizenship. Spain, in particular, had control over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands, Its convoluted history between 1508 and 1898 had dramatic repercussions on its colonial subjects in these islands. The on-and-off application of a Constitution in Spain meant that citizenship was extended and revoked several times since the 1812 propagation of the Constitution of Cádiz.

Prior to the establishment of that constitution, subjects in the Spanish colonies were under varying statuses, ranging from slaves to criollos, all inferior in status to the peninsulares (those born in Spain). The status of colonial subjects was dependent on birth origins and legitimacy. Women, in particular, were bound to the status of their fathers or husbands.

In the US Virgin Islands, Spain also played a role in the question of citizenship, in eliminating the native inhabitants of the islands in 1555 by the order of Charles V. The Spanish Empire abandoned the islands, which allowed Denmark to colonize St. Thomas, St. John, and St. Croix through the Danish West India Company. Lacking a native population, slaves were imported, and the concept of nationality proved more nuanced. Driven by commercial ventures, the administration of these islands varied until 1754, when the Danish crown took official control. Starting in 1775, laws began, on paper, to offer some rights to residents, but their application was lacking.

As time went on, new schemes went into place, which, similar to the Spanish, took into consideration the birth status, origins, and legitimacy of residents in order to obtain citizenship.

American Samoa, on the other hand, did not have European settlements until 1830. The territory itself did not come into existence until a power struggle between the United States, Great Britain, and Germany resulted in the division of Samoa into the present entities of the Independent State of Samoa and the Territory of American Samoa. As such, American Samoa did not experience the same colonial issues involving citizenship as the other territories until much later.

The start of the 20th century then brought major changes for all five territories. Puerto Rico and Guam went to become US possessions in 1898, as did American Samoa in 1900. In 1917, the US purchased the Virgin Islands from Denmark. The Northern Mariana Islands, now separated from Guam, went under German control in 1899 but never obtained German citizenship, then went on to become a Japanese protectorate under similar conditions. They came under US jurisdiction in 1947 with the establishment of the Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands.

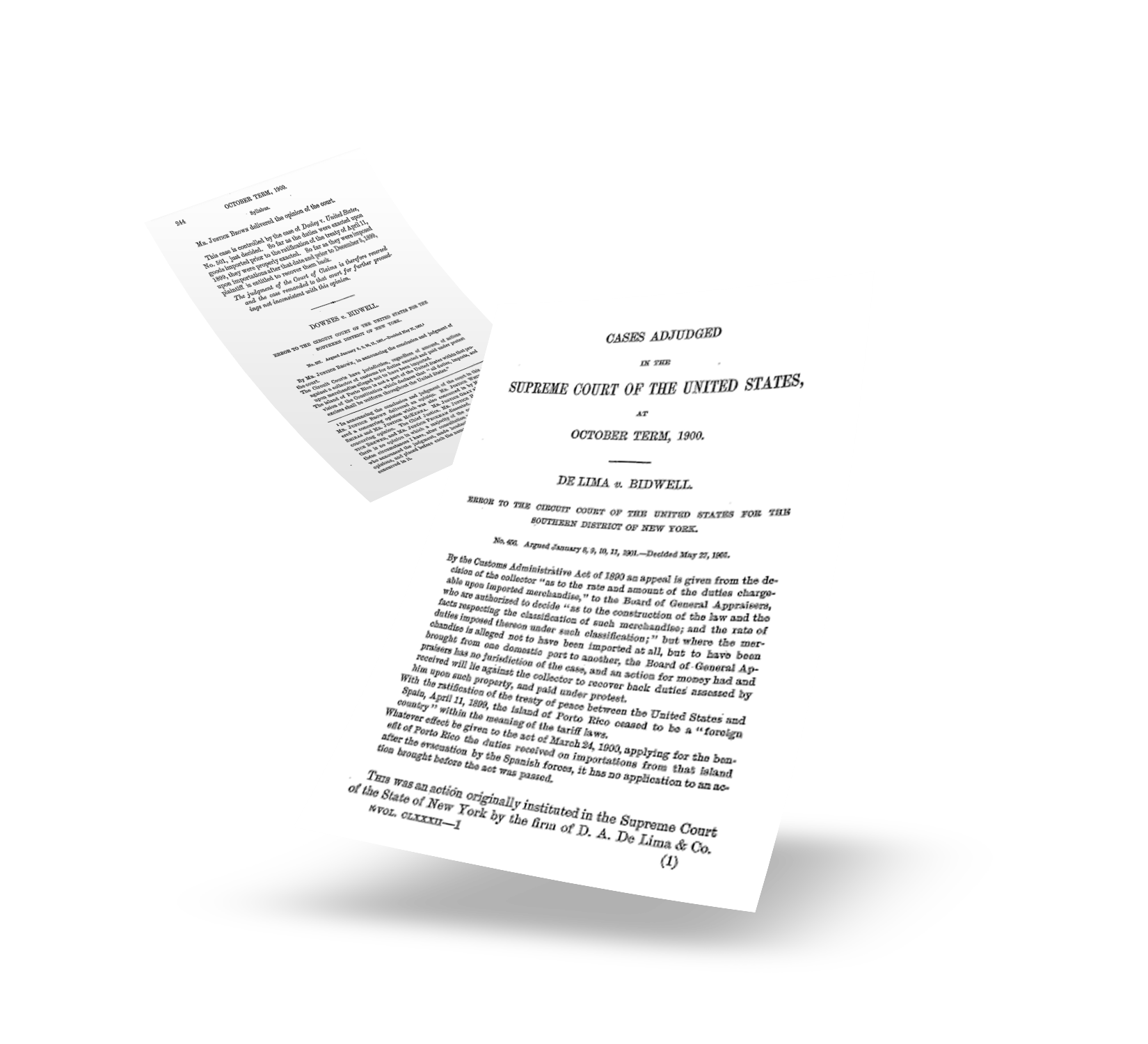

De Lima v. Bidwell and Downes v. Bidwell case rulings.

The Insular Cases and citizenship by court

Prior to 1898, all persons born in US possessions acquired from non-tribal governments had been collectively naturalized by the United States. Then with the Treaty of Paris of 1898 and the advent of US control over Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Philippines, a new territorial-incorporation doctrine was adopted. In essence, residents of the new possessions were no longer to be considered naturalized. This thinking was ratified by the Insular Cases:

- De Lima v. Bidwell

- Goetze v. United States

- Dooley v. United States

- Armstrong v. United States

- Downes v. Bidwell

- Huus v. New York and Porto Rico Steamship Co.

In its decisions on these cases, the Supreme Court of the United States established new jurisprudence, that, among other things, ratified the thinking that the United States Congress had absolute control over the territories pursuant to the Territorial Clause of the US Constitution. In addition, this also meant that the Constitution itself did not apply ex propio vigore—i.e., of its own force—in the newly acquired possessions.

Despite their racist origins—the De Lima v. Bidwell ruling termed people of the islands “savage tribes”—these rulings still govern the United States’ territories.

The issue of citizenship in US territories has since been the subject of several legal cases over the years. For Puerto Rico, the case of Isabel Gonzalez brought the issue of citizenship to the forefront in the late 19th century. Gonzalez, who was born in Puerto Rico, was detained upon her arrival in New York and was not allowed to enter the United States. Her case, Gonzales v. Williams, ultimately led to the passage of the Foraker Act, which granted citizenship to Puerto Ricans but did not give them the right to vote in federal elections.

The establishment of this jurisprudence also enabled changes in the citizenship status of the other territories. American Samoans were considered US nationals since 1900, and since 1906, when the US Congress passed special provisions, persons born in unincorporated territories can be naturalized in the United States.

For the US Virgin Islands, the Act Conferring United States Citizenship on the Virgin Islands of 1927 “collectively naturalized all persons who had renounced Danish nationality by failure to declare a desire to retain it, all natives of the islands who were not nationals of any foreign nation, all natives of the islands residing in the continental United States who were not nationals of any foreign nation, and all persons born in the Virgin Islands on or after 1917 who were US non-citizen nationals.” This act, however, did not extend all rights of the US Constitution and still allowed for the territory to be governed by a military governor until 1931.

Guam residents were also then eligible for naturalization as citizens, but since the process required a court with a seal, clerk, and jurisdictions, which had not been created for the territory, they lacked any practical means to do so. Efforts in Congress failed to get any traction, and it wasn’t until after World War II—and the Japanese occupation of Guam—that through the Organic Act of Guam of 1950, residents could become citizens. The act solidified the interpretations of the Insular Cases.

The unequal treatment between the territories is further exemplified in the case of the Northern Mariana Islands. The territory established a covenant with the United States in which it limited the power of the United States federal government and the application of its laws to those specifically mentioning the Commonwealth that also have the territory’s prior consent. This unique arrangement, however, did not impact the application of citizenship, as upon ratification, US nationality and citizenship were granted.

The ongoing debate

While it may seem that after all branches of the US federal government coalesced around the new scheme of unincorporated territories—and of court and Congressionally-granted citizenship for them—the issue came to be settled, that is not the case. As happened during the turn of the century when this new thinking was implemented, there is an ongoing debate on the details, applicability, and future of this scheme.

Back in 1901, the announcement of the Downes v. Bidwell decision drew what was, at the time, the largest crowd to the Supreme Court. The case also warranted the attention of the media, with newspapers like the New York Herald lambasting the decision that established “one-fourth of the national domain, and ten million people are subject to no law but the will of Congress.” The Denver Post also criticized the ruling for bringing the US into colonial ownership and landing the nation “rank of land grabbing nations of Europe.” The establishment of this order rankled many scholars, politicians, and influential figures who believed it went against the anti-colonial values of the country.

Since then, the debate has far from settled down. Cases like Harris v. Rosario in 1980 saw Justice Thurgood Marshall writing a dissent questioning the Insular Cases. Similarly, in Torres v. Puerto Rico in 1979, Justice William Brennan joined Justice Potter Stewart, Justice Marshall, and Justice Harry Blackmun and wrote that the “concept that the Bill of Rights and other constitutional protections against arbitrary government are inoperative when they become inconvenient or when expediency dictates otherwise is a very dangerous doctrine and if allowed to flourish would destroy the benefit of a written Constitution and undermine the basis of our Government” citing Reid v. Covert.

The debate continues, with citizens from every territory challenging the doctrine of unincorporation set by the Insular Cases. In 2015 a group of American Samoans was denied by the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia in their challenge to obtain birthright citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

Other cases have involved the issue of domestic or subnational citizenship. A prime example was that of the Ramírez de Ferrer v. Mari Brás case in Puerto Rico, which saw a challenge to Juan Mari Bras being eligible to vote in Puerto Rico. Mari Bras, who had been born in Puerto Rico, had renounced his US citizenship in 1994 before the US Consul in Caracas, Venezuela. In said statement, he claimed his status as a citizen of Puerto Rico, which, in his opinion, was consistent with his Puerto Rican nationality. The case ended with the Supreme Court of Puerto Rico establishing that to vote in elections in Puerto Rico, only Puerto Rican citizenship is required, even though the local legislature had established US citizenship as a requirement. Due to this ruling, the Puerto Rico Department of State now issues a Puerto Rican Citizenship Certification upon request, a transaction popular enough to have support groups online to help guide interested citizens.

The existence of this kind of subnational citizenship was also established in Guam when Willis W. Bradley, Jr., who was appointed governor, issued a proclamation in 1930 granting Guamanian citizenship in the territory under certain conditions. Similarly, the Northern Mariana Islands underwent a period in which their domestic nationality had to be defined as they determined their political status.

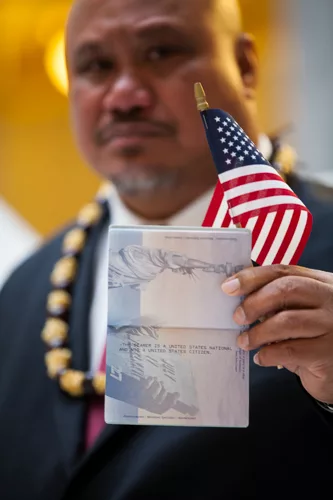

John Fitisemanu holding his American national passport that states: “THE BEARER IS A UNITED STATES NATIONAL AND NOT A UNITED STATES CITIZEN.”

The impact and context of citizenship

The ongoing legal battles and political efforts to further define, redefine, or undo the citizenship scheme for territorial citizens have resulted in very real consequences on the islands. From denials of Constitutional rights, extension of federal benefits to control of immigration, the rulings on this issue dictate fundamental aspects of life in the unincorporated territories.

Take the 1922 case of Balzac v. Porto Rico: It originated when in a district court of Puerto Rico, Jesus Balzac was prosecuted for criminal libel for an article that indirectly referred to the colonial governor Arthur Yager. Balzac was denied a request for a trial by jury due in large part to the established precedent of the Insular Cases. A unanimous Supreme Court of the United States ruled that certain provisions of the Bill of Rights did not apply in Puerto Rico, thereby denying the application of the Sixth Amendment.

In some cases, some rights were affirmed, as happened in 1979 with Torres v. Puerto Rico, when Terry Torres was subject to a search of his bags upon arriving in Puerto Rico. Finding an ounce of marijuana, Torres was convicted and sentenced and proceeded to appeal to the US Supreme Court, arguing the search was a violation of his Fourth Amendment rights. SCOTUS agreed and ruled that there was a full-force application of the guarantee against unreasonable searches and seizures in Puerto Rico.

Because of the fluctuating nature of court decisions, more cases keep coming up seeking enforcement of rights denied under the current precedent. Gregorio Igartua De la Rosa, a citizen of Puerto Rico, has filed several cases seeking to enfranchise the residents of Puerto Rico in federal elections, failing each time due to stare decisis, the foundational concept in the American legal system to honor precedent.

With similar intent, organizations like Equally American continue assisting citizens seeking to expand the right to vote in federal elections to US territories and extend birthright citizenship to the territories, including in American Samoa. Despite these recent efforts, SCOTUS has remained steadfast in its upholding of precedent, declining to review the Insular Cases. In cases like United States v. Vaello Madero, which sought to extend Supplement Security Income benefits to residents of Puerto Rico under the equal protection clause of the Constitution, the court has ruled to uphold the unequal treatment of the territories. The ruling in this case by Justice Brett Kavanaugh even pointed out that this differential treatment in laws is sometimes not detrimental, as is the case in the exemption of federal income taxes for residents of the territory.

“In devising tax and benefits programs, it is reasonable for Congress to take account of the general balance of benefits to and burdens on the residents of Puerto Rico,” Kavanaugh wrote.

In another recent case, the court again declined to revise the standing order when a group of American Samoans once again sought to extend birthright citizenship to the territories.

This lack of citizenship can have a significant impact on the lives of people living in American Samoa particularly. For example, US nationals are not allowed to vote in federal elections, and they do not have the same rights as citizens when it comes to federal benefits. They are also ineligible for certain offices.

On the other hand, this structure also enables the territory certain privileges, such as having its own immigration law (unlike any other US jurisdiction). This power helped the territory be one of the last places on the planet and the last US polity to register a COVID-19 case. Central to this issue is also the territory’s ability to maintain native costumes on issues like land ownership. Under American Samoan law, Native land ownership is restricted to those who are at least one-half native Samoan.

To officials in the American Samoan islands, an automatic extension of US citizenship would endanger customs like these. That is why in cases like Fitisemanu v. United States, they have staunchly opposed any efforts to extend citizenship to the territory.

The politics of citizenship

Affecting everything from historical events, travel, and economic circumstances to identity itself, it is no wonder that the issue of citizenship is also a major political issue. As the situation stands, the US court system seems unmovable in its decision to maintain the status quo until Congress, through the political process, changes it.

Even with Justices Neil Gorsuch and Sonia Sotomayor asking for SCOTUS to reconsider the Insular Cases, it will likely take political action for change to happen. And it will likely have to originate in the territories themselves.

Puerto Rico might be the territory where this might be the most likely to happen. This was especially clear during the recent consideration of the Puerto Rico Status Act in the US House of Representatives. The questions surrounding the future of US citizenship in the territory should it choose to become an independent nation, even with a possible compact of free association, continue to fuel debate. Some even questioned the constitutionality of the bill due to its provisions on citizenship under an independent Puerto Rico.

Absent action by federal entities, it might require local activism to seek a settlement to this issue. History has shown that even though for most of their history, the issue and context of citizenship have been decided by colonial powers with little to no insight from locals, their voices can spark change. Suffragists in Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands like Isabel Andreu de Aguilar, Rosario Bellber, Milagros Benet de Mewton, Bertha C. Boschulte, Ella Gifft, Eulalie Stevens, and Edith L. Williams can be directly attributed to legislative and court activity that enfranchised women because of their citizenship.

That said, settlement is a subjective concept, and what that looks like for each of the territories will vary. The idiosyncrasies of American Samoa vary from those in the US Virgin Islands. Northern Mariana Islanders might be more at ease with the present situation than some Puerto Ricans. One certain aspect: Issues of political representation, federal aid and services, and cultural identity, among others, will continue to shape the debate.

In the context of the last decade, as things change or stay the same on this topic, one thing is clear—few, if any, other discussions dictate life in the territories as much as that of citizenship.

This is the second in a series of articles examining the United States and its relationship with the territories, marking a decade after Pasquines’ founding. Please help us continue covering the context of islands by making a donation today.

1. This is an excellent presentation of the ongoing issue of off-shore American citizens not being allowed to vote in the U.S. Presidential election, although we offer land and political partnership as the defensive echelon against U.S. adversaries from mainland Asia, e.g., China, etc. When would American’s phobic mentality go away and treat the “Territories” as first class U.S. citizens, on the par with those in the mainland U.S.A.