What does it mean to be an American? Is it a question of perception, of citizenship, or of ideas? For Puerto Rico, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands, the context of identity is a particularly complex subject, as is the norm with life in the United States unincorporated territories. Colonization, diversity, and politics have played influential roles in the formation of the collective and individual concepts of identities in these islands in ways that transcend time and space.

What flag one feels represented by, which passport one uses when traveling, or what culture one feels closest to are different ways to think about the idea of identity. For each territory the answer to this question can vary, even within each territory, depending on political leanings, life experiences, or, sometimes, the sport being played. What does hold true for all territories, however, is a similar pathway through history.

From indigenous-held lands to colonized jurisdictions, today, the island territories of the US constantly debate and struggle with the definition of their identity in cultural, linguistic, and legal forums. Because of this, there is no simple definition of the concept of identity, let alone a uniform answer to the question of how does one identify. However, in examining the history, perspectives, paradoxes, and future of identity in the islands, there are many valuable lessons to be learned.

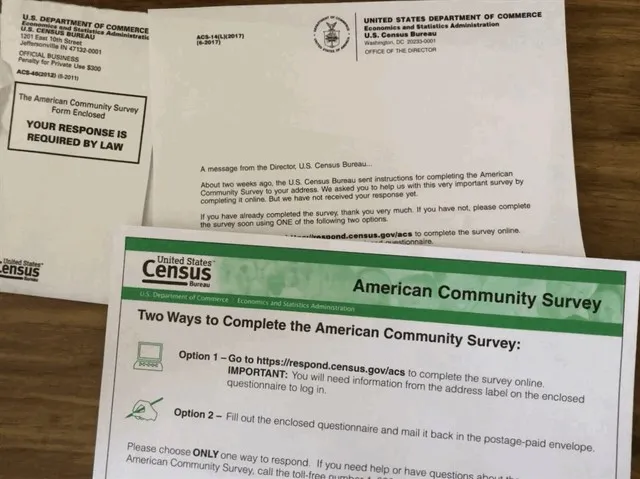

A village of Taínos in Puerto Rico, also known as yucayeques. Photo credit: hablemosdeculturas.com

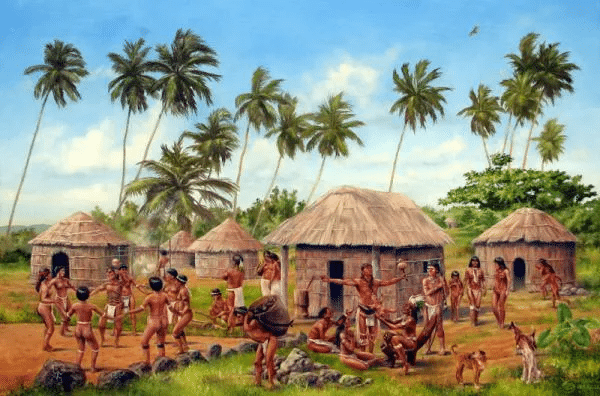

Ancient CHamoru in Guam. Photo credit: The Guam Gallery of Art

Girls Carrying a Canoe, Vaiala in Samoa

Origins of identity in the territories

Before the advent of colonialism in the islands we now call US unincorporated territories, the context of identity was a simpler one. For Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands, the Taíno ruled; for Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, the CHamoru; and for the American Samoa, the Samoans. These cultures developed and existed for thousands of years, developing symbiotic and interdependent relationships with their environment that shaped their own self-image, and now play important roles in shaping contemporaneous perspectives of identity.

For instance, although there is still debate on the origin of the term Taíno, there is some consensus that it means “men of the good.” We also know they called St. Croix in the US Virgin Islands Ay Ay, or “the river,” and Puerto Rico, Boriken, or “the great land of the valiant and noble Lord.” This is why Puerto Ricans are also colloquially known as Boricuas. This direct correlation of self-identity during indigenous control of the islands to modern times perfectly encapsulates how historical events have shaped, defined, and redefined the identity dynamics at play.

A similar story played out with the precolonial society of the Mariana Islands, which was based on a caste system. In that system, Chamori was the name of the ruling, highest caste. Following colonization by the Spanish, the name became the exonym Chamorro, or endonym CHamoru. Guam’s name also comes from their language, as they called the island Guåhan. And in the case of the Northern Mariana Islands, a traditional clothing item of the Carolinian people, the mwar mwar, shows up on their flag.

For the territory that had the latest contact with European civilizations, the influence and impact of the indigenous civilization are undeniable—their systems still govern daily life in the islands. For Samoans, or the “people of the ocean or deep sea,” in American Samoa and the neighboring state of Samoa, faʻa Sāmoa and fa ‘amatai are the current cultural and governing systems, both based on the welfare of the ‘aiga, or family.

To varying but undeniable degrees, the development of these native cultures would prove definitive in the formation and development of the concept of identity in the territories. As existential challenges arrived on the shores of the islands, the resilience of these cultures shone through, likely due to the fact that they developed over hundreds if not thousands of years. Despite the incredible obstacles to their continued existence that history has and continues to deliver, these original identities may have been the most influential for the territories.

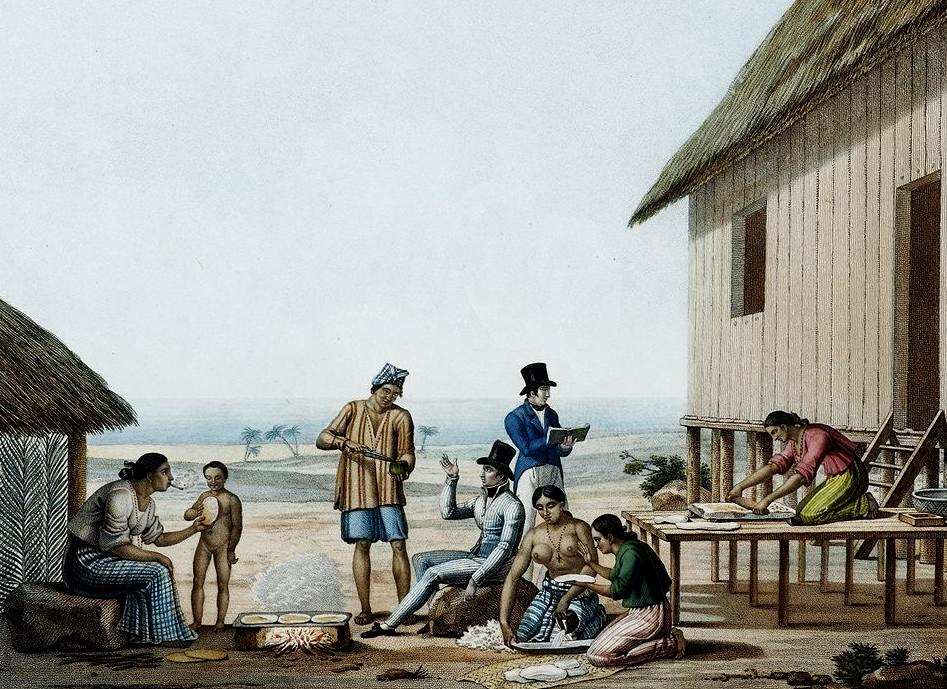

View of the the Spanish colonial era in the Marianas picturing both the Chamorros and the elegantly dressed Spanish. Photo credit: Historical Boys’ Clothing

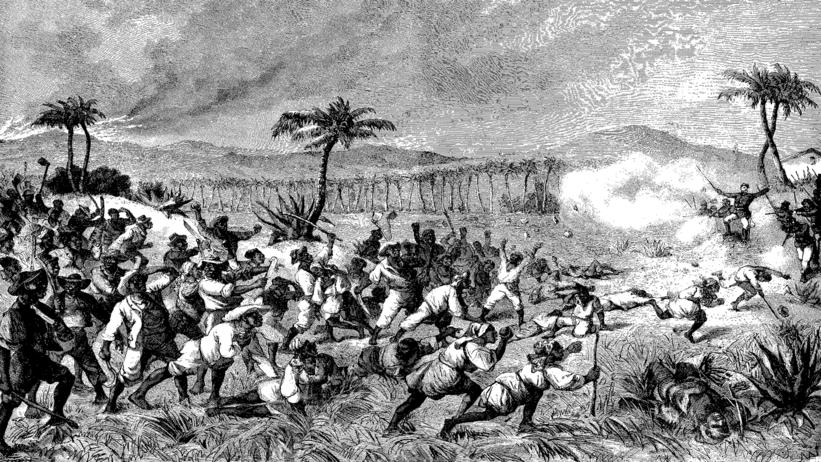

The Revolt on St. Croix.

Christopher Columbus kneeling, holding the flag of the Crown of Castile and sword with two other men holding flags.

Contact with colonization

As we have seen before, the established, developed, and stabilized systems that governed life in the insular areas that are now under US jurisdiction were all upended by the onset of European contact and colonialism. Cultural, social, and political structures all endured drastic changes that would forever change how inhabitants of these islands viewed themselves and how they were seen. Perhaps ironically, however, it is in this period that we get to learn the most about what had been there before and how it changed in every one of the territories.

The appearance of the Spanish, and their subsequent impositions, in three of the territories profoundly impacted life in them. Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands were all subjugated to the whims of an empire that had no issue eradicating language, customs, traditions, and entire societies that did not align with its interests. In that process, new components of identity in the colonies appear with a long-lasting legacy.

The changes imposed by Spain are most visible and evident in Puerto Rico. Slavery, disease, and cultural impositions all but decimated the Taíno population in less than 50 years. Boriken was no longer Boriken, but instead San Juan Bautista, and then Puerto Rico (the island and its capital switched names after Christopher Columbus appeared on its shores). Under the authority of the King of Spain and the Pope, the process of colonizing began to expand the Spanish Empire and the Christian faith. Despite laws in Spain meant to protect indigenous people, the establishment of the encomienda system forced labor, and infectious diseases had brought down the Taíno population.

The introduction of slaves from African nations to replace the Taíno labor force then added the third element of what is conventionally known as the racial makeup of modern Puerto Ricans. In reality, it also precipitated immigration from places like France, Ireland, Corsica, and Germany. For the neighboring US Virgin Islands, initially disputed by Spain, France, Britain, and the Netherlands, smaller populations of Taíno and Carib similarly disappeared. Then with the islands coming under Dutch control, the havoc of colonialism took hold.

On the Pacific, Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands under Spanish rule also saw native populations decline by more than 90%. People from the Philippines and the Caroline Islands were then brought in to repopulate the islands. These new ethnic makeups brought with them cultural, linguistic, and social changes that determined the makeup of modern residents of the territories. This is particularly evident in areas like religion, with Catholics making up 75% of Guam’s population.

In this respect, it is American Samoa where to the greatest degree, the native culture has remained as intact as possible, withstanding contact with European cultures. Like in the Marianas, however, it has adapted to the principles and teachings of Christianity.

Having endured the consequences of first contact with European civilizations and the subsequent colonialism, the identity in the territories would then transform with the advent of US control. Although at very different times and through varying circumstances, US acquisition of these islands would prove as impactful as native and initial colonial components to the context of identity that exists today in every territory.

American Samoa at the South Pacific Games. Photo credit: Fatumafuti on Wikipedia

Today’s context of identity

Today, identity in the US territories is a complex tapestry interwoven with diverse influences. Residents of these islands navigate multiple layers, including indigenous heritage, colonial legacies and their current effects, along with contemporary cultural dynamics. The territories’ unique blend of local customs, languages, and traditions coexists with the pervasive influence of American culture and values. The tension between preserving indigenous identity and embracing global influences shapes the ongoing discourse surrounding the concept in these regions.

The US territories grapple with various challenges and paradoxes when it comes to identity. Cultural assimilation, language preservation, political status, economic dependency, and the interplay between tradition and modernity are all factors that shape the identity landscape. The delicate balance between celebrating cultural heritage and adapting to evolving societal norms can create tensions and paradoxes that require careful navigation.

Depending on the territory, the issue, and the particular conversation, identity can take a different meaning. And the discussions on these issues take place in many forms, from academic to legal and purely practical purposes. Add in political leanings, and the debates sometimes take passionate and explosive characteristics that, in some cases, hinder thoughtful conversations.

Even for a territory like American Samoa, arguably the one with the least amount of colonial influence, the impact of its existence as US jurisdiction is undeniable. Locals have embraced aspects of US culture, in sports particularly, with American Samoans thriving in American Football. American Samoans are more likely than any other jurisdiction to produce American Football players. Yet despite having the term ‘American’ in its name, the territory has difficult ongoing debates about its identity and its practical implications.

Being the only US territory without birthright citizenship, it enjoys freedoms in terms of governance that have allowed core indigenous concepts to endure. It also means that the question of whether residents are Americans can be a complex one. Although able to travel freely to the mainland US and other US territories, they cannot do so with REAL ID cards. American Samoans also cannot work most federal government jobs that required citizenship, and cannot hold public office outside their territory, unless they naturalize. On this issue, opinions are torn between those wanting to preserve local traditions, and those seeking automatic citizenship at birth. The debate is ongoing, as court cases and political movements seek to address the matter once and for all.

Add in matters of language, and the debate on identity takes on a whole new level of complexity. For some American Samoans, that can make adjusting to life in the mainland more difficult. For Puerto Rico, it becomes the root of severe differences in self and collective identity, political persuasions, and beyond. As the only one of the territories where English is not the dominant language in daily life, interesting perspectives have developed. For instance, in Spanish, it is commonplace for locals, including the media and politicians who recognize the colonial situation of the islands, to refer to the territory as a ‘país,’ the word for country, despite the fact that Puerto Rico lacks the common traits of sovereign countries. The term is used synonimously with that of being a nation, which arguably is better suited to describe the existence of the Puerto Rican culture and ethnic identity without delving into the political status issue.

The debate on the use of the term gets even more complex when it comes to issues like international representation. While on legal and political matters the US is who represents Puerto Rico and the other territories, on areas like sports or beauty pageants, that is not the case. Puerto Rico (like Guam, the US Virgin Islands, and American Samoa) has its own International Olympic Committee, and can participate on its own in the Olympics. The territory also sends a separate representative to the Miss Universe pageant, and is currently the third highest winning jurisdiction in the pageant. These are fiercely defended points of pride that then, somewhat surprisingly, influence debates on matters like the future political status of Puerto Rico.

Find a Puerto Rican on Twitter, and their political status preference for the islands will likely be evident right away from which flag emojis they have on their profile. A Puerto Rican flag by itself? That person is likely pro-independence. A Puerto Rico and US flag? You’re likely looking at a statehooder. These self-identifications then are marked by debates on matters like international representation, use of language, and even which version of the Puerto Rican flag you use. Yes, even which is the correct tone of blue to use in the flag is a debate influence by political status preference (this in turn facilitated by both a lack of official standards, and the past repression by the US of the flag itself).

These are but just a few examples of how the influence of the US has created this tense environment, of conflicting local and national identities. Factor in matters like migration, race, and the larger framework of American identity itself, and the complexity of the matter is ever-increasing. Given the freedom of movement between the islands and the states, for example, there are now more self-identifying Puerto Ricans in the mainland itself than in Puerto Rico proper. This causes intense debates on authenticity, voting rights, and even matters as practical as the acceptance of Puerto Rico IDs stateside.

Consider then debates on racial identity, and how national conversations don’t always have the same effect or understanding in Puerto Rico. Differing viewpoints have emphasized different aspects of identity as the defining traits for the concept itself, with no definitive consensus on what should determine the answer to the question of what are the residents of Puerto Rico and the other territories. Similar conversations extend from the waters of the Atlantic to the Pacific.

For Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands, there are also studies and discussions on the effects of Indigenous identity, colonialism, and politics on their own identities. What it means to be a CHamoru given the intricacies both territories face is not a settled question. Understanding that, is essential to engaging in these conversations that happen every day in academic, informal, and legal forums.

This complex dynamic wherein their identity as American citizens is juxtaposed with their limited political power manifests itself as pervasive cultural issues. The ongoing discussion surrounding political status and the quest for self-determination is deeply intertwined with the islands’ collective identity and aspirations. And that is now shaping narratives about the future, what should be a focus, and where locals ought to dedicate themselves in an effort to protect their culture.

Analyzing and understanding the past, present, and potential future for each territory, has emerged as a priority, like in the US Virgin Islands. Recognizing the intersectional aspect of being a resident of a US territory and the recognition of diverse identities has similarly taken hold in recent conversations. Given the context of being an unincorporated territory of the US and its consequences, concerns on belonging and preservation are part of the conversation as well.

Despite the challenges, the territories have also witnessed vibrant efforts to affirm and celebrate their identities. Cultural festivals, language revitalization programs, and community initiatives play a vital role in preserving and promoting local heritage. The rise of grassroots movements and advocacy groups also demonstrates a growing desire among residents to assert their own narratives and shape their own identity narratives after centuries of outside factors being the deciding factors.

Given their shared experience, there has also been a rise in recognizing the similarities the territories face, and ways the exploration of the concept of identity can be mutually beneficial. Exploring nationalism in American Samoa and Puerto Rico, or the latter’s similarities with the US Virgin Islands have become self-empowering exercises meant to draw useful lessons.

Issues of identity in the US territories today are multifaceted and complex, shaped by historical, cultural, and political factors. From negotiating local and national identities to preserving cultural heritage, the territories face ongoing challenges in defining and asserting their distinct identities. However, through community resilience, cultural initiatives, and efforts for political representation, the territories are actively shaping their own narratives and working towards a more inclusive and empowered future.

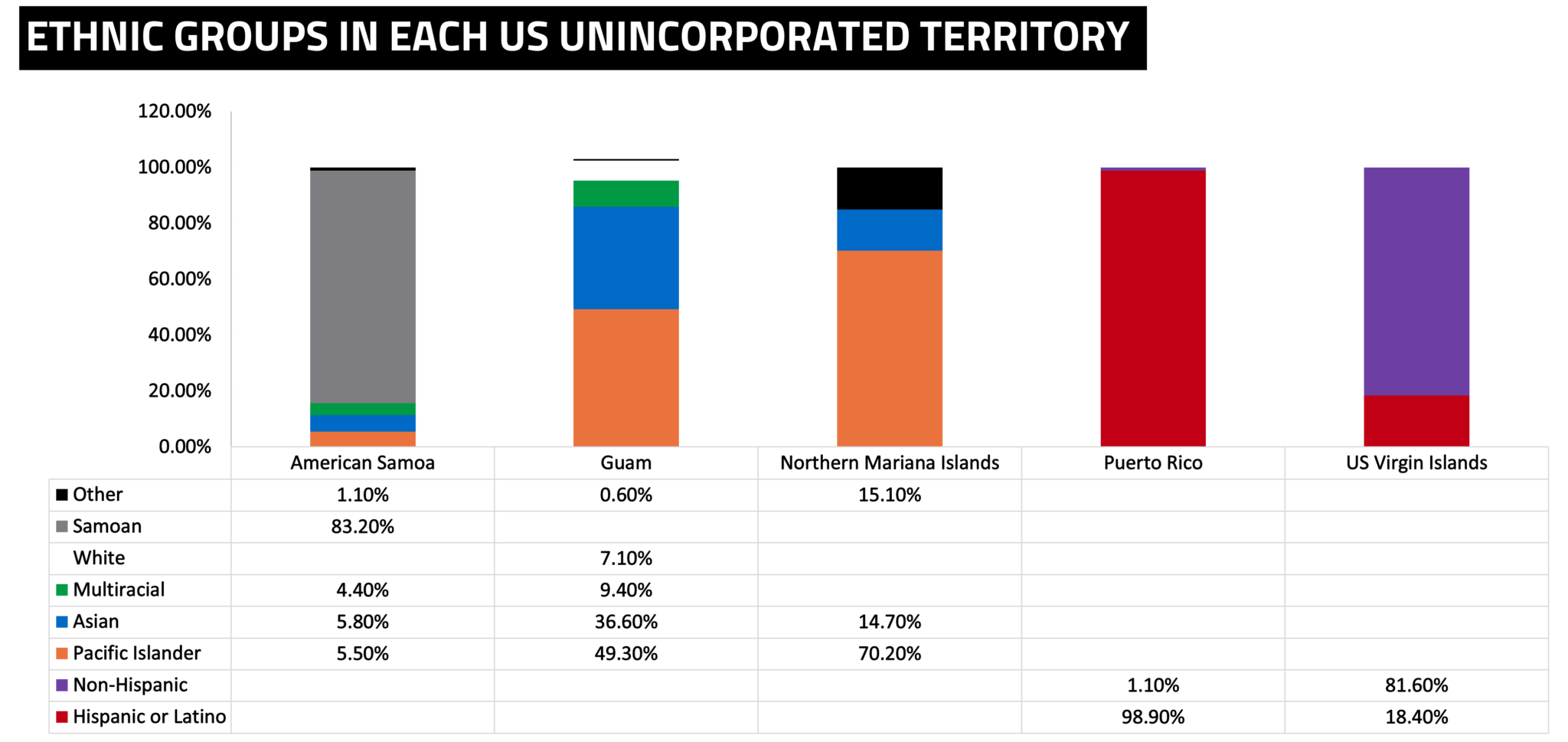

Ethnic groups in each US territory. Source: The World Factbook

Evolving identity

The future perspectives of identity in the US territories offer glimpses of hope, resilience, and transformation. Even amidst challenges like salient cultural stress, as the territories navigate their complex histories and contemporary challenges, several trends and movements are shaping the future context of identity.

One significant aspect is the resurgence of indigenous identity, with a growing recognition and celebration of indigenous heritage and cultures in the territories. Native communities are reclaiming their languages, revitalizing traditional practices, and asserting their rights to self-determination. This resurgence not only strengthens the fabric of local identities but also fosters a deeper connection to the land and ancestral traditions.

Multiculturalism is also playing a crucial role; with diverse communities and historical ties to different nations, the territories are becoming melting pots of cultures, languages, and traditions. This multicultural tapestry contributes to the richness and vibrancy of local identities. In places like the US Virgin Islands and Puerto Rico, the blending of African, European, and Indigenous influences has given rise to unique cultural expressions and a sense of shared identity that transcends borders.

Diaspora communities from the territories are also influencing the future of identity. Individuals and families who have migrated to the mainland US or other parts of the world maintain strong connections to their homeland. These diaspora communities actively contribute to the preservation of cultural practices, language, and traditions. They serve as bridges between the territories and the wider world, fostering a sense of belonging and fostering transnational identities.

As the territories assert their distinct cultures and histories, there is a growing recognition of the need for self-determination and autonomy. Calls for political representation, decolonization, and greater decision-making power are gaining momentum. The future holds potential shifts in the relationship between the territories and the United States, fostering more inclusive and empowered identities that reflect the aspirations of the residents.

The future perspectives of identity in the US territories are marked by the resurgence of indigenous identity, the celebration of multiculturalism, the influence of diaspora communities, the evolution of notions of national and local identities, and inclusive movements for preservation and self-determination. As the territories continue to navigate their complex histories and forge their futures, these trends are shaping a diverse and dynamic tapestry of identities that reflect the unique heritage, aspirations, and resilience of the residents.

This is the sixth in a series of articles examining the United States and its relationship with the territories, marking a decade after Pasquines’ founding. Please help us continue covering the context of islands by making a donation today.

0 Comments