As island paradises, the unincorporated territories of the United States have many commonalities in several respects. Beyond history, politics, and perception, the very nature of Puerto Rico, Guam, the US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, and the Northern Mariana Islands has a remarkably similar story to tell. These insular areas have developed into unique, biodiverse, and dynamic ecosystems that, throughout their history, have faced many of the same dangers and challenges.

From tropical rainforests to coral reefs, the landscapes of the US territories are havens for species found nowhere else in the world. As such, they have been especially vulnerable to outside factors ever since each of the islands was colonized by Western powers. Now, the lasting consequences of colonization, along with the present dangers of development and the future threat of climate change, might be the greatest challenge in the context of conservation these territories face.

In reviewing the history and experience of every one of these places, however, one finds not only examples of lessons learned but stories of success and recovery, even from the brink of disaster. And in every single territory, the concerted effort to protect and conserve natural resources is seen by public and private entities alike. As challenges, old and new, jeopardize the treasures that have developed over millennia, hope and optimism are not unreasonable given the context of efforts to protect what makes these islands such beautiful places.

The natural context of conservation

In the progression of the natural development of the island territories, the relationship between the native indigenous inhabitants and their environment was, arguably, a sustainable one. An examination of the biological diversity of the territories throughout their history reveals cultures that depended on their natural environment, understood that dependence, and took measures to ensure a sustainable relationship with their environment. This understanding shaped not only spiritual beliefs but practical applications and customs, which, although ignored at first by colonizing powers, still have lessons in today’s world.

This careful and methodical management of natural resources by native cultures was true across all territories. Even so, in ways that might be shocking in terms of today’s conditions. Take, for instance, species that today are considered endangered, like the Iguaca (Puerto Rican Amazon) parrot, or the West Indian Manatee, both of which were food sources for the Taíno that inhabited Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands. The population numbers of both species used to be much higher in pre-colonial times, a testament to the measured approach the indigenous culture had when it came to managing their resources.

This also extended to agriculture and farming. For thousands of years, before European colonizers arrived on the shores of the Caribbean, the Taíno had learned how to manage the land properly. They would use techniques involving slash-and-burn cultivations, along with ‘conucos,’ which were piles or mounds formed from years of conch and other food debris to cultivate in. These mounds, in particular, allowed them to obtain a significant yield increase in terms of agricultural production while maintaining the soil’s fertility and preventing over-farming. The implementation of these techniques not only facilitated their sustenance but represented a significant societal advancement, allowing for leisure time for other activities, but was also one of the few cultivation systems with environmental conservation as a trait.

Consequently, these practices were an integral part of the Taíno culture and beliefs that ensured their advancement and development in the region, even if it was ignored when the Spanish arrived.

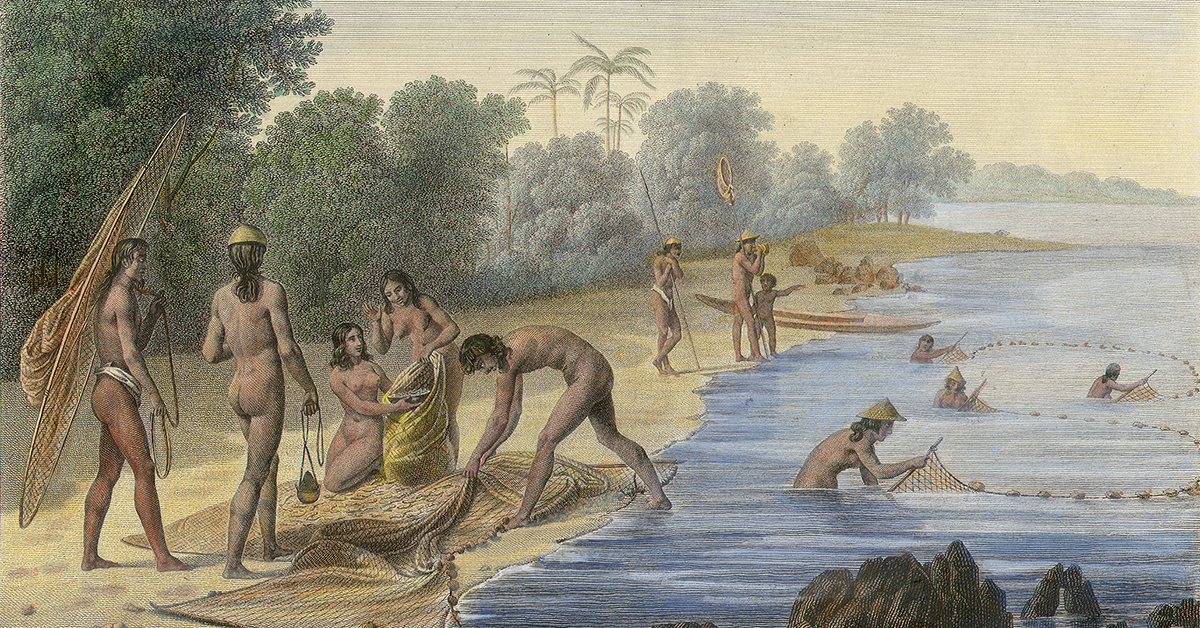

A very similar philosophy and mindset played out in the Samoan islands before colonization. In American Samoa, today, the area with the greatest marine biodiversity in the US, for more than 3,000 years, the culture was “rooted in a respect for and reliance on the environment.” Under Fa`a-Samoa, or the cultural context that governs life in the islands, there is a great emphasis on the community and its welfare. Among its several aspects is the ancient concept of tapu. This concept regulated the activities of this oceanic culture that relied heavily on fishing (and still does to this day, although to a lesser degree). In order to protect resources, areas that were overstressed became off-limits for fishing activities, using seasons and lunar periods as guides.

This traditional knowledge, like with the Taíno, was quintessential to life in the Samoan archipelago.

Then there were the “taotao tano,” or people of the land: The CHamoru people of the Mariana Islands. The Marianas—today Guam and the Northern Mariana Islands—have been their ancestral homelands for more than 4,000 years and, as such, are the soul of their culture. Consequently, the CHamoru believed in an essence in Nature, one which they attempted to live in harmony with, given the interdependence involved.

Like the Taíno in the Caribbean, the CHamoru also utilized resources that today are in rare supply. The fanini, a fruit bat, and the fadang, a cycad plant—both endangered and found only in the Marianas—were regular staples of their diet and closely tied to cultural traditions.

But as with matters like perception, citizenship, ideas, and tourism, colonization would arrive to fundamentally alter matters in the territories and in the context of conservation, strictly and objectively, for the worst.

Caribbean monk seal, which inhabited the Caribbean and went extinct in 1967.

Challenges, old and new

In examining ecosystems, scientists can identify indicator species, “organisms whose presence, absence or abundance reflects a specific environmental condition.” These can serve as a tool to examine the health and overall condition of a particular area. For the territories, several species then serve as a historical record of the consequences of the arrival of the European colonizing powers. Their practices involving the exploitation of natural resources for short-term economic gain, along with the dismissal and then elimination of indigenous practices, have had lasting consequences that pose significant risks today.

Take, for instance, the aforementioned Puerto Rican parrot. Prior to the arrival of Christopher Columbus, estimates had the population numbering anywhere from 100,000 to 1 million individuals. Then as humans increased their population, settlements spread through the islands, and forest land diminished, problems started; Likewise, with the sustainable agriculture that the Taíno had been practicing for thousands of years. The shift from subsistence farming to resource exploitation for the benefit of Spain had detrimental consequences for the conservation of Puerto Rico’s resources in so many ways that it ended the Taíno, and the parrots have almost gone extinct.

The pattern of extracting resources without the consent of indigenous people and the nefarious aftermath played out across the world and is still a topic of discussion. Even in cases where there wasn’t a direct exploitation of resources, as was the case with the Spanish and their mercantilist hacienda system, natural resources have still been severely impacted by colonization. Invasive species, cultural changes, and an increase in human activity dramatically altered the environment of these islands.

Consider the case of the Mariana Islands’ fruit bats. Their population managed to sustain itself even with the hunting practices of CHamoru, up until World War I. Then with the US and its technological war advancement came calamity. With guns, local islanders were able to hunt in far greater numbers, plummeting the population size of the animals, which happen to be the only major seed disperser for cycad plants like the fadang. Now, difficult conversations happen about how to approach the situation, with differing perspectives on whether to prioritize native customs or conservation.

The consequences of interfering with balanced relationships with nature then become evident. These effects keep cascading as new challenges come up. As the world now turns its attention to climate change, the line from resource exploitation in the 16th century to a globally changing climate as a consequence of human activity is direct.

The failure to adopt principles of sustainability and responsible stewardship from indigenous culture has been a defining aspect of global resource management in the modern world. And scientists have now established the direct correlation between colonialism and climate change, declaring that “historic and ongoing forms of colonialism have helped to increase the vulnerability of specific people and places.”

Rising global inequities, deforestation, and pollution can all be attributed to colonialism. The effects are pervasive and lasting, and the relatively recent recognition of this fact is now starting to have its own effect. As the effects of the new existential challenge for the planet start showing up, especially in places like the US territories, lessons are now being drawn from the history that was once ignored.

Already there have been drastic impacts on the biodiversity and ecological health of the insular areas of the US. Rising sea levels, extreme weather events, and habitat degradation are significantly altering the ecosystems of islands across the US and the world. But now, there is a recognition that we can implement techniques and customs from ancestral civilizations to restore at least part of what makes the US territories such incredible places.

As part of that realization, there have been discoveries that warrant some level of optimism. Even from the brink of disaster, efforts to restore, protect, and sustain the ecological systems that these islands have developed have shown their worthiness. This is now marking a shift in the framing of conservation, from an effort often imposed and enacted without local and indigenous input to one that requires the participation of those most impacted by the decisions made on this topic.

And for the US territories in particular, these conversations are taking an existential tone, both in terms of actual subsistence and identity.

Trunk Bay, US Virgin Islands National Park. Photo credit: Kent Kanouse

Dedication to success in conservation

Search for organizations, programs, and initiatives involving conservation and protection efforts in the territories, and you will find resources galore. With the epiphany of needing to protect natural resources, there is a plethora of groups working to ensure the survival of species, ecosystems, and conservation itself. Federal and local agencies, nonprofit organizations, and activists are investing money, time, and effort in spades to conserve the resources we have.

For each of the five territories, there are dedicated initiatives to protect species, ranges, and nature itself. They take the form of government programs in Guam monitoring reefs, engaging in cultural outreach, and reintroducing species to their natural habitats. The situation is similar in the neighboring Northern Mariana Islands, where discussions, reports, and conferences are happening with the same objectives. Groups like Pacific Bird Conservation and the National Association of State Foresters are also present.

In American Samoa, there is a National Park and a National Marine Sanctuary, along with plans to protect the fisheries that sustain so much of its economy and lifestyle. Nonprofit groups and even films are dedicated to efforts in arguably the most remote of the US territories, all focusing on learning from the past to step up efforts for the future.

Looking at the Atlantic, you can already find measures of success from these dedicated efforts. For the US Virgin Islands, research is showing key fish species are benefitting from conservation initiatives. The territory has even recently won international recognition for its “environmental education and information, water quality, environmental management, and safety and services.”

In Puerto Rico, you can even find some measures of reversing, to some degree, the consequences of the errors from the past. Having reached a population low of 13 individuals in 1975, the Puerto Rican parrot is now under a recovery plan that has brought its numbers to around 500, even with recent setbacks. These successes should serve as inspiration and justification for the organizations, collaborations, and plans to continue investing in conservation across the territory.

Debate still occurs on this issue, but there seems to be a consensus developing in the territories and globally on the importance of conservation, learning from ancient cultures, and the implementation of that wisdom.

Jean-Michel Cousteau, Sylvia Earle, and Nainoa Thompson explain how important it is to educate and inspire kids to take part in ocean conservation because they will be the future decision-makers.

Future of challenges and opportunities for conservation

Looking to the future, conservation efforts in the US territories will need to focus on promoting sustainable development and involving local communities in decision-making processes. The impacts of climate change will also need to be addressed through adaptation and mitigation strategies. The integration of traditional ecological knowledge and practices must also play a critical role for there to be a chance of success.

Federal funds are now pouring into the islands with a clear intent to protect the natural environment in the territories as climate change poses new threats. And while there are still differences in perspectives as to handling conservation and economic development, as exemplified by the recent concern of the territorial governors of the Pacific regarding the potential expansion of a marine sanctuary in the US economic exclusive zones of the Pacific Remote Island Areas, the direction of future efforts seems certain.

Future generations will require sustaining these initiatives, as their success will be essential for the continued subsistence of life in the territories in more ways than one. From being able to survive weather events, preserving cultural heritage, and maintaining the very identity of the territories themselves, the lessons of the past must be respected, honored, and implemented. Successful conservation efforts in these territories demonstrate that it is possible to preserve and protect these biodiverse landscapes. As we look forward, a collaborative approach that involves local communities and promotes sustainable development will be critical to ensuring the long-term conservation of the US territories and beyond.

This is the fifth in a series of articles examining the United States and its relationship with the territories, marking a decade after Pasquines’ founding. Please help us continue covering the context of islands by making a donation today.

0 Comments